Who Am I?

My story starts in the first grade where I would draw a little paper plane on the top left corner of the paper I was writing on. I have been an artist for as long as i can remember I just didn't realise it back then that art was going to save my life one day.

I moved to Pune ( Maharashtra) to pursue mechanical engineering in 2010. I was scared at first and then I tasted freedom. I had never been away from home and I had recently been released from the hospital. I was 18 years old in a new city meeting other awkward middle class boys. I still cannot put a finger on what exactly encouraged us but on a random day a few of us decided to paint a huge wall on campus for the college Fest and convinced our seniors to buy us sufficient paint. This was the first ever mural I painted and I loved the process. Though it turned out to be ugly and hence we never clicked any pictures of it. We repainted that wall every year and it eventually became a cultural trend for the coming batches.

Engineering came easily to me. The first three years were a breeze. But my interest in art kept increasing exponentially—and so did the differences between my father and me. Once my father stopped giving me allowance I was pretty much on my own. First I lost respect amongst friends because I couldn’t pay for my share of food or rent or basically anything. Then I started to experience what real hunger meant. I had to go from one friend’s house to another for food, one friend’s couch to another to sleep. It was embarrassing. Many nights I had spent wandering on the streets because I had nowhere to go. I didn’t have any choice so I took up any job I got. I whitewashed walls at construction sites. I painted pretty flowers on the walls of small roadside tea stalls. I made custom portraits for people. I even did other students' college assignments. I was just trying to survive one day at a time.

By the time my fourth and final year of engineering was coming to an end I had decided to take up art as a full time career but I had no prospects. I had missed enough classes that I knew I was not graduating. I saw all my friends either getting jobs or moving abroad for higher studies. I was scared, ashamed and obviously couldn’t go back home so I didn’t.

I started going door to door with printouts of photos of the walls I had painted in college, looking for work as an artist. Back then, no one had even heard of the concept of mural painting in India. Cafes, bars, studios, housing societies, play schools—I tried everything. For the next two years, I had no place to call home. I had run out of clothes to wear, and the little work I got paid very little. I had lost all my friends. I was always hungry and wouldn’t eat unless someone else offered me food. I spent nights on footpaths, in office corridors, and at under-construction sites where I was working. By then, I had stopped buying packaged water and was drinking straight from taps. I had lost my self-esteem, my confidence—and a lot of weight.

I was angry—angry at the whole world. Choosing art as a career had brought me nothing but insults. Insults from family, from friends. Everyone looked down on me. I was outcast, dismissed, completely unsupported—and on top of that, they all called me crazy. I took a pledge: I would live life on my own terms and earn every rupee only through art.

One of those days, I found myself at the JJ School of Arts in Bombay, looking for a job. I waited outside the director’s office for hours until he finally called me in. That day, he gave me advice I’ll never forget. He said there was very little scope for art in our country—most artists either become professors or give up on art altogether. But he told me he saw a spark, a hunger in me, and that if I could somehow survive the next ten years, by hook or by crook, I would be able to make something of myself. And in the end, it would all be worth it.

I’m now going into my eleventh year since that day.

I was born in a small town called Arakkonam in Tamil Nadu India on 24th August 1992. My father served the Indian Navy , hence we moved between Tamil Nadu and Goa until I was 17 years old. I didn’t grow up in an environment suited to become an artist. Artists are supposedly fearless. We were scared. Scared of inflation, scared of society, scared of change, scared of speaking up. So I preferred to stay quiet. I was good at studies , I was expected to be, I worked hard at math and science specially. But I do not remember what made me draw every Sunday , quietly without letting anyone in my house or school know that I loved drawing. At this point I had no idea that art was a real career in the world outside of my bubble.

I got courageous during my first encounter with cancer in 12th grade (2009) when I was 17 years old. For the first time in my life I wasn’t living at home. I was admitted in a military hospital surrounded by older military cadets and officers and I was learning about life outside of my school books for the very first time. It was exciting. One of my newly formed older friends gave me a novel to read. This was my first ever non school curriculum book I read. “The White Tiger” by Aravind Adiga. This was my introduction to art or I must say literature. I never stopped reading after that.

I fought second stage Hodgkin’s Lymphoma throughout my 12th grade and won. Thankfully I didn’t perform well in any of my college competitive exams, couldn't get into any prestigious engineering college and joined the one that took me in. Symbiosis Institute of Technology . Which now I understand was my first step towards becoming a professional artist.

By February 2016, I had already been experiencing weakness and breathlessness for weeks, but I kept ignoring it because I had to keep looking for work to survive. One day, when I couldn’t climb a flight of stairs, I knew something was wrong. I had already crossed the age limit to be eligible for military hospital services, but I still went to the army hospital because I couldn’t afford a private one.

The cancer had relapsed, and this time it was stage-four Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. This time, I was scared. I was desperate to make it as an artist. I wanted to prove the world wrong. I wanted to earn back the respect I had lost over the years. I didn’t want to depend on anyone—I was too proud. And most importantly, I didn’t want to die before making something of myself.

The first year of treatment was experimental. Doctors tried various combinations of chemotherapy, but nothing seemed to work. I kept seeking second, third, even fourth opinions—but no one really had a solution. My health was deteriorating day by day: constant nausea, fever, loose motions, and overwhelming weakness. I didn’t even care about losing my hair. The cancer had reached my brain.

On my birthday, I had requested to be taken to the mall. As soon as we arrived and I began walking toward the entrance, I felt a numbing sensation on my face. I turned back, and by the time I reached the car, my body froze. The worst part—I was conscious but paralyzed. I had never felt that helpless before. My eyes were weeping, but I couldn’t move a muscle.

I had these episodes often, until one day, a doctor at Tata Memorial Hospital suggested an experimental drug called Brentuximab, which had to be imported from Germany. Given the financial condition my father and I were in, we couldn’t afford the medicine. We used every resource we had, called in every favour we could. I begged, borrowed—did whatever it took—and somehow, we managed to get a few vials of the drug. For the first time after a year of failed treatments, my reports showed a reduction in cancer cells.

I was advised that better blood reports were not enough, even if the cancer cell reduces I will need a Bone Marrow Transplant aka Stem Cell Transplant to ensure that it doesn’t relapse again.

I was moved to a special hospital dedicated to BMT (Bone Marrow Transplant) patients. At the time, I had no idea how long the procedure would take. I was informed that the survival rate for this procedure was just 30%, and given my condition, my doctor warned me that I was unlikely to survive. But I still chose to go ahead with it.

For the first 30 days, I was kept in complete isolation—no one was allowed to see me except the doctors. I wasn’t allowed to eat or even sip water. Everything my body needed was delivered through a special catheter surgically inserted directly into my heart, which remained there for over a year.

Ten patients, including myself, began the BMT procedure together, and by the end of the first 30 days, only three of us had survived. For the next year, I lived in the hospital without stepping outside the premises even once. I lost count of how many patients I saw die during my stay—and somehow, I kept making it through each checkpoint. The doctors told me it was a miracle; they admitted they had never really had any hope for me.

Throughout the treatment, I had a lot of time on my hands. I sketched whenever I had the energy—trying to complete at least one sketch a day. I felt that without a sense of purpose, I wouldn’t survive it. I also held onto a small hope that someday I would return to my normal life, and I didn’t want to waste these days. I was still optimistic that I could make it as an artist one day.

I was finally allowed to go home. I went to stay with my parents in Mumbai. I had gained a lot of weight because of steroids. I didn’t like the way I looked.

One day, during one of my regular walks by the sea, I was sitting on a bench when I noticed two men walking past me. They stopped near the bench next to mine. While one of them sat down immediately, I saw the other man carefully examining the bench with his hands before taking a seat. That’s when I realized he was blind. In that moment, I felt a sense of relief—despite everything I had been through over the years, at least I could still see the beautiful sunset in front of me.

I stood up to head back home—and I couldn’t walk. My legs couldn’t bear my weight. After a few X-rays, the doctor introduced me to my new problem: Avascular Necrosis. It was a condition where my hip bones had collapsed due to a lack of blood supply, a side effect of the excessive steroids I was given during the BMT.

I was made to understand that a small percentage of BMT patients do encounter this condition, and that I could still live a normal life after undergoing hip replacement surgeries. However, I wasn’t fit enough to go under the knife at that point—so I focused on making paintings instead.

As another side effect, I found it increasingly difficult to maintain a firm grip with my fingers. I was dropping spoons while eating, unable to write, and couldn’t hold a paintbrush properly. So I decided to create abstract paintings by dripping paint, inspired by Jackson Pollock.

The next page is a small selection from the 100 such paintings I created over the following months—leading to my first solo exhibition.

I was then invited by TEDx to deliver a talk about my life—specifically on the topic of being Stoic, which I pretty much am. It was the first time I was treated with such respect. I had been working for so many years, sharing my journey on Instagram, but I never thought anyone was really paying attention. Turns out, some people were.

As soon as I shed the excess weight and was able to walk on my own—even if with a limp and bearable pain—I left my parents’ house and returned to Pune, the city where I had originally started my career, to begin all over again. It wasn’t easy, but I had a friend and his family who gave me shelter for months, until I could afford to live on my own.

In order to get noticed, I declared that I would paint 100 murals across the city as part of an initiative to clean and beautify Pune. I was desperate to get back to the wall—to feel it all over again. I craved the feeling of people noticing my work. I wanted to exist, to have an identity—and what better way than to paint the whole city? So, with a bag full of spray paints and a foldable stool, I set out every day, limping my way through the city, one wall at a time.

Before I knew it, I was on a road trip across the country, painting wherever someone invited or commissioned me to. After journeying across the country, I returned to my place of birth, where I painted the largest wall of my life. Standing before that towering canvas, pouring myself into every stroke, I felt something shift. For the first time in years, I wasn’t just surviving—I was reclaiming myself. That experience filled me with a quiet, unwavering confidence for what I was about to do next.

Ever since I stepped into the world of art as a career, everyone has asked me, “How will you make money?” I’ve always heard, “There’s no money in art!” I come from a section of society where anything that hasn’t been done before among us is considered impossible. Phrases like “This only happens in movies,” “It takes money to make money,” and “We are working-class people; we can’t start a business,” are commonly heard.

Once, while I was admitted to the hospital, an art-enthusiast doctor asked me if I was someone like Michelangelo, since I paint walls. I was excited to tell him everything I do. But just as I started talking about it, my father held my hand and said, “Come back to earth.” It was deeply demotivating.

Even if we manage to do one or two good projects, art is still seen as an unstable career. Artists are often looked down upon as people lacking discipline—people disconnected from reality, unreliable, and incapable of getting things done. I have countless examples of how badly I was treated just because of this perception. And believe me, these weren’t constructive criticisms; they were gut-wrenching comments that push dreamers away from their path. These attitudes have forced many artists to take up jobs they never wanted, turning them into mediocre employees, living unfulfilled lives.

Such discouragement creates unhappy husbands and fathers—people who can’t guide their children properly, and in turn, raise new generations of fearful, anxious, and directionless individuals. My own father wanted to be an actor but ended up in the armed forces. He was miserable most of his life and passed that same misery, anxiety, and disbelief onto me.

Not just him—most of his colleagues and even my friends’ parents urged me to be “practical” and take up an engineering job. They would say, “If you earn a stable income from your job, you can do art on the side.” No one ever truly understood what I was trying to create—what it meant to have a career where you love what you do, where you’re not forced to work, but excited to.

Every artist would agree—they can’t live without creating. Their schedules don’t follow day or night; they create all the time. That’s the life I wanted. I wanted to own my time. But in my situation, money was a priority—even just to afford canvas, paint, and especially the time to make a painting of my choice.

So I took it as a challenge—not just to talk the talk, but to walk the walk. And the first step was to distance myself from all that discouragement. To walk away from everyone who wasn’t part of the tribe I aspired to belong to.

Books became my allies. Entrepreneurial stories were my mentors. I found thoughts and advice in books that I couldn’t find in my real world. I made a group of friends in the form of books: Think and Grow Rich, Zero to One, The Tatas, Alpha Girls, Shoe Dog, Steve Jobs, Around the Corner to Around the World—these became my circle, my advisors. None of these were art books, because I was already learning art on the job. What I needed was to build a sustainable business so I could create art freely.

My mission became to prove that art is a real career. I couldn’t live with myself if I wasn’t working to change that narrative.

My inspiration came from companies like Infosys and TCS—places where every engineering graduate in India knows they can apply, and if selected, they’ll have a secure career in tech. I wanted to build the Infosys of art—a place where any graduate artist, uncertain of what to do next, can find work they love, earn a stable income, and still have time to create original art. A place where they never have to rely on odd jobs to support themselves.

“Why Paper Plane?”

“A paper plane, even when crafted with precision, remains fragile. It needs a push. It drifts from one room to another, covering only short distances at a time. But a paper plane doesn’t crawl, walk, or run—its destiny is to fly.”

Selling paintings wasn’t an easy business model. First, I had to afford art supplies; then, after completing a painting, I had to spend more on gallery exhibitions and marketing to sell them. It wasn’t a viable business model from the beginning. That’s why I focused more on securing commissioned murals—that was my strength.

For commissioned murals, I charged an advance payment before starting the design work. Clients hired me based on my portfolio, which I had developed extensively by then. This approach made perfect business sense, ensuring commitment from both sides and covering initial expenses.

I found Vijay in Lonavala (a hill station near Mumbai), where he was staying as a tenant at my friend’s Airbnb. Over time, Vijay turned out to be exactly the person I needed to help run the art business. He’s good at the things I’m not—especially operations and accounts.

I’ve learned that as business owners, we need to learn to delegate and find the right person for each job. Vijay was the right fit for the role he took on. This principle of delegation is what has kept Paper Plane running. We always try to find the best person for the job.

As I always say, we have to make a system—not be the system.

We started by making logos. It wasn’t a great year for muralists—COVID had hit the market hard. So I took what I could get. Slowly, the market began to open up, and we started getting smaller projects.

Then came a big break: a major project in Nigeria. I couldn’t go because of my cancer history, but my whole team went. That project was proof that we could function as a company—and that I didn’t always need to be present for the job to get done. From that point on, we never looked back.

Since then, we’ve expanded into creating installations and sculptures, producing VFX and CGI videos for companies and brand ads, and even working with Augmented Reality. We’ve collaborated with numerous prominent brands operating in India.

Last year, we painted the largest mural in Asia—it was the most challenging project we’ve executed, with just five team members (artists).

We’ve been running Paper Plane exactly as I had envisioned. We advertise, acquire clients, and follow a structured workflow—from the initial client call to site visits, preparation, execution, and final handover. We prioritize our artists’ well-being and consistently deliver a little more than what our clients expect.

Paper Plane has been growing year after year, and every now and then, when I take a moment to myself amidst this chaos, I feel extremely thankful that I am living my dream.

My first memory of my wife, Rhea, is that she used to be the manager of my favourite bar in Pune. Super active, super talkative—a short girl running around the bar, serving drinks, talking to everyone at every table. She was the life of the party, every day, all days of the week. She had so much energy that I was actually nervous to talk to her, so I would ask my friends to speak to her if I needed something.

She knew about my hip and was incredibly kind. Even without me asking, she would bring me a cushion to sit on and always gave me a corner table because I loved reading there with my beer. We’ve even had many business meetings at that bar. Friends would come and go, clients too, but I would sit there for hours reading—and that’s when Rhea and I started talking.

She once asked me to make a painting of two cats for her, which I still haven’t painted. Another time, she got me drunk and I promised to cook for her—which I did, and maybe that’s what did the trick.

We got married on 27th July 2022, at her bar. After signing the papers in court that morning, all our friends and family gathered there to celebrate—because Rhea didn’t want her staff—the servers, bartenders, and housekeepers—to be left out of the celebration. So, instead of a big fat Indian wedding, we chose something simpler, more personal. We all celebrated under the same roof where we first met.

One of the days before the wedding, I was in Delhi painting a mural for a phone brand. It was a big project—being professionally shot for a TV advertisement—so I was completely swamped. At one point, I was up on a boom lift, 30 feet in the air, in the middle of a take with cameras all around me, when my phone started ringing. It was Rhea. I figured it must be an emergency, so I picked up the call mid-shoot. And then she says, “We have a cat now.” Just like that. We named her Daku, which means dacoit in Hindi—you’ll know exactly why when you see her face.

Most of my family an

d friends thought I would never get married. Not just because of my past, but because they didn’t see me as the marrying kind. On some days, even I believed no one would actually want to marry me. And it wasn’t without reason—who would want to marry a guy who has almost died multiple times, has a limp, probably can’t have children, and works in art—a field that, in India, is often seen as lacking both respect and stability?

But then Rhea happened.

Rhea is a person entirely of her own will. She didn’t care about any of that. She didn’t need her parents’ permission or society’s approval. She loved me for who I was, and that’s all that mattered to her. She has a childlike energy—something I think I lost in myself over a decade ago. She brings life to my otherwise mundane days. I don’t talk much, and she talks enough for the both of us. I don’t really cherish things, and she celebrates even the smallest events—like buying vegetables.

I needed her in my life to remind me how to appreciate living. To enjoy the little things again.

Rhea loves food. She could travel across countries for it—and she has. From local Indian street food to cuisines from every corner of the world, she knows it all. And she cooks like an artist. It’s not just something she enjoys—it’s something she needs to do, like a painter or a writer who can’t live without creating. The kitchen is her element. She won’t tolerate compromise when it comes to her cooking. Everything has to be just right—the perfect ingredients, precise measurements, and a kind of enthusiasm that never fades.

Rhea is also the reason I started travelling. It’s not always easy with the limp, but she makes it feel effortless. We went to Turkey for our honeymoon, and it remains the best trip we’ve had so far. That journey didn’t just give us memories—it became the inspiration behind many of my paintings.

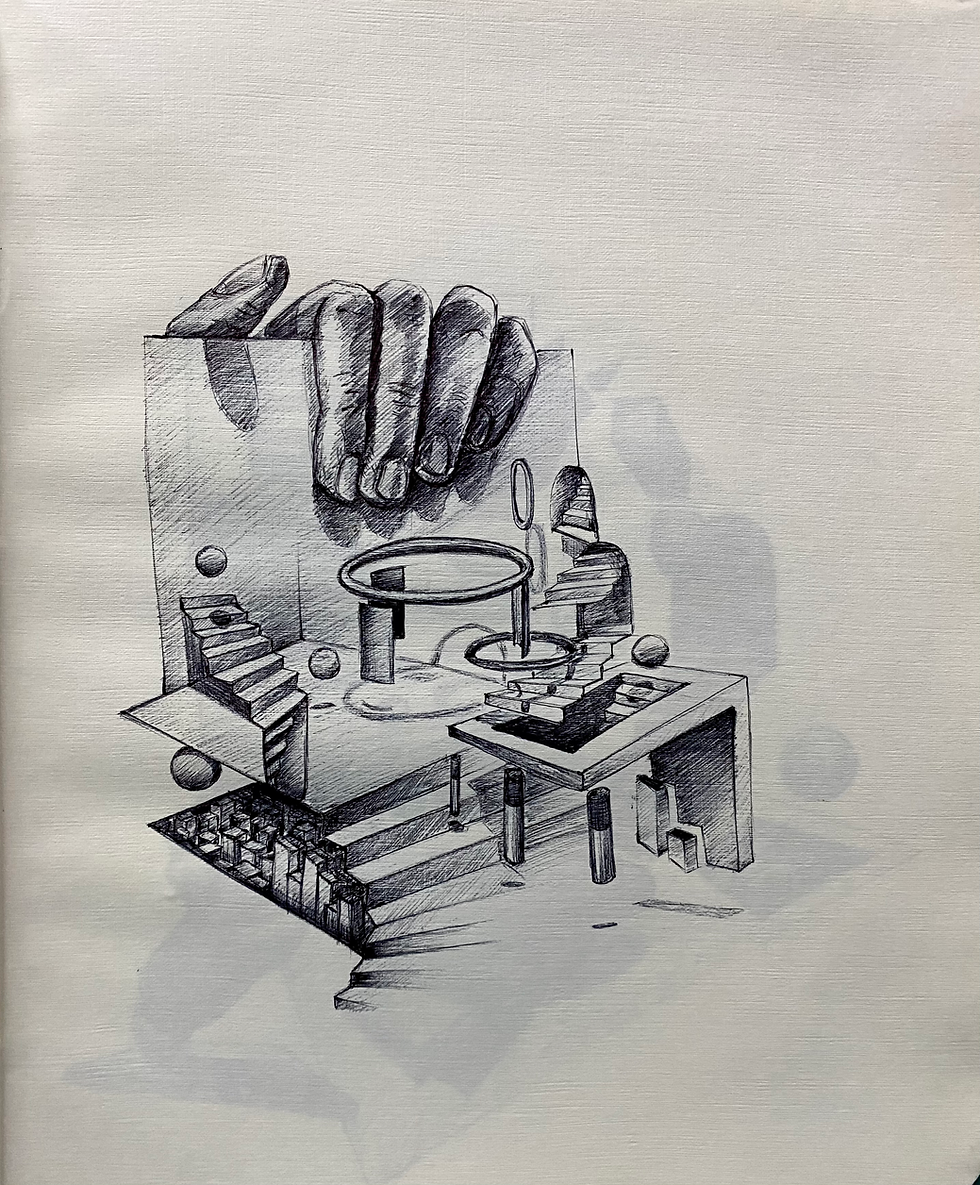

Ever since I was a child, I don’t think I was ever truly at ease with the world around me. Though I have happy memories and some truly wonderful friends, looking back, I’ve always felt like I was trying to create my own little world within the one I was living in. That longing has deeply influenced my art. From my earliest sketches to the paintings I create now, everything revolves around building a world of my own.

Surrealists have had a huge impact on me—MC Escher, Rob Gonsalves, Dalí, René Magritte. They all painted realities of their own, and I’ve always been fascinated by how far the human mind can stretch. I believe that what seems impossible to one person is completely achievable to another—and surrealism became my way of reaching those possibilities. It gave me the freedom to paint what exists only in my mind. A world I don’t have to explain to anyone. A space that’s entirely mine.

My surrealist work comes from a place of pure honesty. It’s deeply personal—shaped by my thoughts and emotions, untouched by the noise of the outside world. Every artwork that follows has been created with heart, and for no one else but myself.

My life took a drastic turn at the age of 17 when I was diagnosed with cancer, along with an abnormality in my heart. For the first time, I didn’t have to study—and in that pause, I found space to truly explore art.

Although I initially enrolled in engineering, seeing it as a practical career path, my passion for art eventually pulled me in a different direction—one of self-discovery and creative expression. I was driven by a deep desire to pursue this calling. Even though I had no formal experience, I sought guidance, embraced every opportunity to learn, and slowly immersed myself in the world of graffiti. My determination and commitment helped me develop my skills and build a solid foundation in this dynamic art form.

After completing my engineering degree, I made the bold decision to pursue art professionally. In 2016, I founded my own art company—but fate had other plans. On the very day I officially incorporated the company, I received the news of a relapse. I was now facing the last stage of cancer. What followed were years spent in and out of hospitals, battling not just cancer, but temporary paralysis and avascular necrosis.

Through all of this, I realized that building a career in art could be just as intense and demanding as fighting cancer. I started approaching my artistic practice with the same discipline and strategy one would apply to business. With a vision to elevate the status of art and create meaningful opportunities for fellow artists, I assembled a dedicated team to take on large-scale mural projects—ensuring not only high creative standards but also consistent income for everyone involved.

Today, I continue to navigate physical challenges, but I remain deeply committed to my mission: to build an environment where all artists can thrive, work full-time on their craft, and no longer have to rely on unrelated jobs to support their passion. My company has collaborated with top brands both in India and abroad, and I take pride in the strong presence we’ve established in the creative industry. Resilience and purpose fuel everything I do.

About the artwork

My body of work is defined by a unique approach to painting, where I primarily use spray cans on canvas. This choice of medium is deeply connected to my roots as a graffiti artist—a foundation that continues to influence both my techniques and visual language. Spray paint allows me to create fluid gradients, seamless transitions, and a polished finish that gives my canvases a striking sense of depth and vibrancy. While spray paint is traditionally associated with street art, I’ve refined its application in my studio practice, bridging the gap between urban expressionism and contemporary fine art.

At the heart of my artistic vision is my engagement with surrealism, which I see as both a method and a philosophy. My work is a vivid exploration of the relationship between the external world and my inner consciousness. I draw from memories, dreams, and abstract thoughts to reimagine the familiar and construct alternate realities that challenge conventional perspectives. Each painting I create becomes a portal into a deeply personal, dreamlike universe—rich with symbolism, emotion, and metaphor.

Through these imagined realms, I invite viewers to reflect more deeply on reality and the subconscious. My art is not only a celebration of creative freedom but also a testament to the power of visual storytelling in expressing the intangible.

Transforming Spaces with Art

Discover More As a Member